Dugald Cameron; Artist, Pilot and Man of Influence.

My first meeting with a man I’ve held in high regard since I was a wee boy, was a complete surprise to me and full of the kind of Bohemian confidence I love. I was doing my thing in the cafe when a voice behind me asked ‘Are you the aviator?” “Aye said I. It quickly became apparent to me without any formal introduction, that I was speaking to the one and only Dugald Cameron, professor and holder of an OBE. It made my day that he had come in for for a blether.

The elegant lady he was with smiled and went to sit at the table to order for them both with the kind of acceptance that showed this was a familiar scene; she had lost him, again, for a while as he chatted about flying and art.

It took time to get together again for a proper interview, but for me at least it was worth the wait. Dugald’s life story could fill a book, it has in fact, so I’ll not try to replicate that here. His fame from my perspective, came from his drawings and paintings of the aeroplanes that he so clearly loves, which is a story in itself.

I’d heard a tale that must have been in the mid 80’s, that he had once been told off by a teacher for drawing aeroplanes on his school jotters. Apparently the teacher told him, “You’ll never make anything of yourself drawing planes.” I asked him if it was true, “not entirely” was the sum total of the reply. It’s a good story though as drawing aeroplanes led to a career that included being the head of the Glasgow School of Art.

The interview began with me on the receiving end of a question!

An Interview with Dugald.

Dugald: So why do you want to know about me and what are you going to do with this?

Jim; I am fascinated by all forms of flight, so I have a website dedicated to flying in Scotland. Whatever method you use to get off the ground, we are united by geography and I aim to document that. This latest project has a focus on the people that make the scene interesting and unique. I thought that you would be a great person to start with, you are the first in the series.

Dugald; In my view there are three things that make for an interesting person, Enthusiasm, Eccentricity and the pursuit of excellence, wrapped up in a casing of curiosity of course.

Jim; I find that assessment a sound one to run with. I have known you most as the artist behind Squadron Prints, can you tell me about how that started?

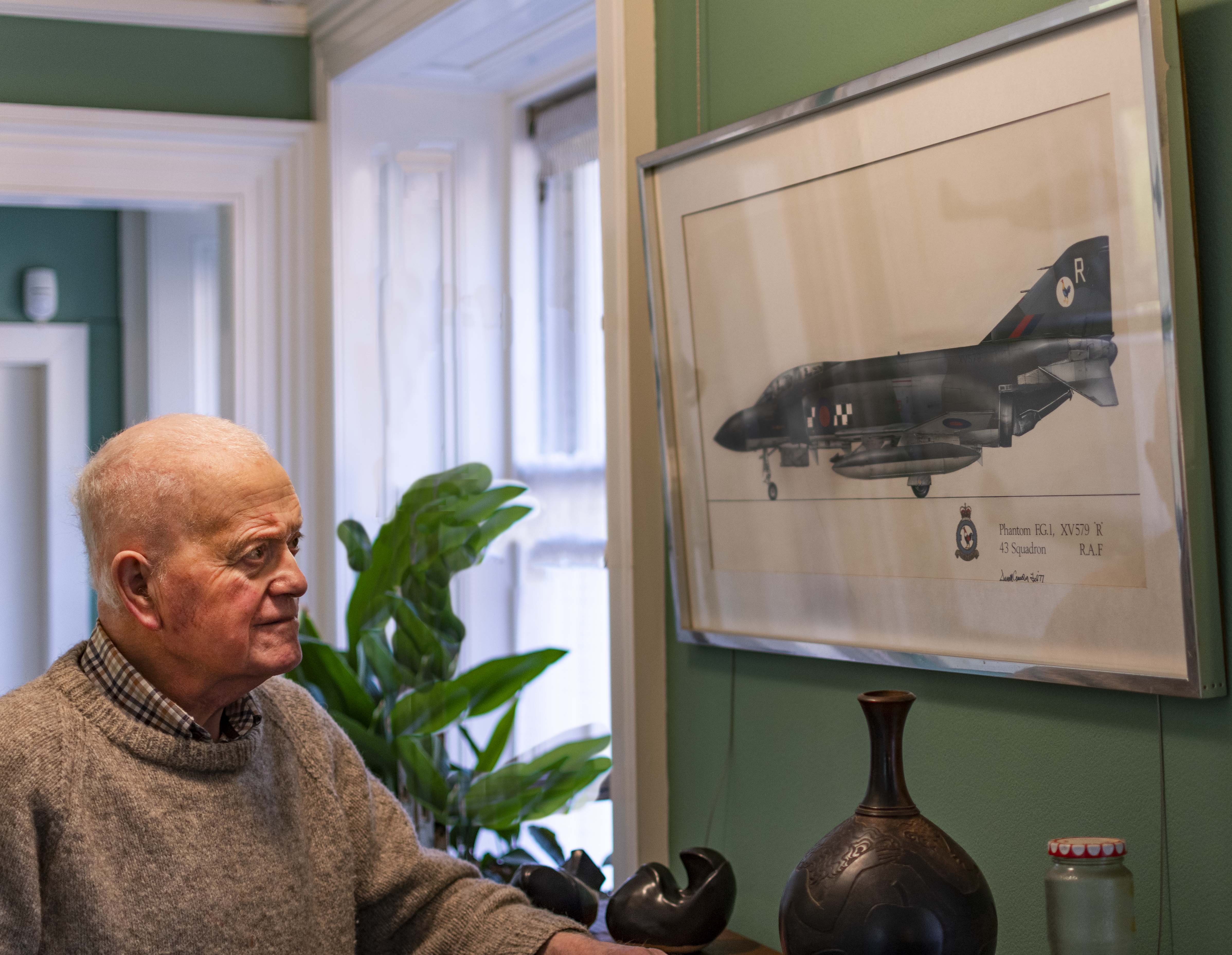

Dugald: Among my other interests and activities I was in the Volunteer Reserve of the RAF with the Air Cadets. I managed to informally arrange a trip in a Phantom, that really was an experience. I decided to draw one of the aircraft from 43 Squadron, complete with oil streaks, dings and aberrations that well used machines acquire over time. You know the misaligned camouflage on the panels and such like. I decided to make some prints and donate them to 43 Squadron for fundraising purposes. I had access to a printing company with my friend Alan Carlaw so it was easily done.

Jim: It’s fair to say the trip made a lasting impression.

Dugald: Those prints were so popular that more were ordered and that started a series of about 750, mostly drawn by me but some were other people. Some were variations of existing ones, but that’s how Squadron Prints came about. I had had a very close relationship with the RAF and with Leuchars in particular through the company, they were very helpful. I am really grateful for all of their support.

Years later when I was President of the Prestwick branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society, I met Air Chief Marshal Sir Steven Hillier who was the Chief of Air Staff during the 100th anniversary year. Interestingly he comes from Kilmarnock as did his number two in the RAF, Air Marshal Sir Stuart Atha, which is unprecedented.

Not Always a Smooth Ride.

I remember we had an order from 4 Squadron when they had the Harrier. They had artwork on the fin, red and black with a lightning flash in between. I went down for a visit and took some photographs of one machine to work with. Once I was finished I saw another picture of a Harrier from the squadron and the red and black parts were the other way round. I called them up and after a quick check out the window the reply came back; “You’re right enough, the others have all been painted differently to the original, what are we going to do?” I told him he that he now had two thousand prints but only twelve aeroplanes and left it up to him.

I also managed a full day with a freshly painted Concorde in a hangar in London, it was pristine and really beautiful. I had an order for 250,000 prints for British Airways. I said to Alan that we needed to get this right and there could be no mistakes. It all got signed off but when I checked before sending them out there was a single letter typo mistake. I was gutted. We sent them off and it was never picked up by anyone at BA.. We thought about that and decided that this was such a big deal for a really prestigious client that it had to be right. We decided to do the whole run again with the mistake removed.

“We did the things that we wanted to do, not the things that were necessarily profitable.”

Jim; I love that sentiment, we could all do with some more of what we love.

Dugald: Alan and I took a print of the Battle of Britain memorial Flight Lancaster with us to Prestwick Airshow in 1976 to give to the crew. The skipper loved it and asked us if we wanted to come up during the show. Too right I did! I took the mid upper position, flanked by a Spitfire and a Hurricane, it was incredible. It really brought home what those people did back then.

Jim: It’s not just aircraft though that you drew is it?

Dugald; No, we did a lot of ships for the Royal Navy as well. I spent a lot of time and got a lot of great access to them, particularly the Ark Royal. I became a connoisseur of submarines too as I saw so many from my house on the Clyde. HMS Dreadnaught was doing some slow speed trials along the measured mile so I drew her and sent a copy to the crew at Faslane. I got a call from the first officer asking me along for drinks. That led to an offer from the Captain to come along on the first leg of a patrol, I couldn’t believe it. They were going from Faslane to Liverpool and said I could come along. I had a conference in London that tied in nicely so I was really keen to go. It was a slow and relaxed overnight trip, no hurry. The scopes and radar screens all had hoods over them to preserve the Captain’s night vision, it was very dark.

I handed in my expenses to the Council for National Academic Awards and it read, train fare Glasgow to Faslane. Faslane to Liverpool by SSN Dreadnaught, £1.50 which was the equivalent train fare and then my rail ticket from Liverpool to London. They all thought I was having them on but paid it anyway.

Art Finances Flying...

Jim When did you learn to fly?

Dugald: 1969, that was a great year, first flight of Concorde, first flight of the 747 and man landed on the moon. I had a commission for a design so I just thought of a price, it was agreed with no quibble so I knew exactly what to do. I was down at Glasgow airport from April to September getting my licence. Most people fly as they can afford to but this let me complete the course quickly.

I was flying a Beagle Pup not long after that trying to impress a young lady. We got to one hundred feet and the engine started spluttering and farting so I got the nose down quickly. There was still runway left in front of me so we got down no problem. I was wondering what was going on as I had done all the checks and I knew everyone could see and hear this happening. As we taxied back the engine kept running but what a noise it made. It turned out that the tanks had been filled with a water and methanol mix as well as avgas. The tanker had three compartments, two with avgas and one with this mix to help jets perform better in hot weather. Someone had left the cross flow valve open and we got a contaminated mixture.

"Flying teaches you an awful lot."

Jim: Do you still fly?

Dugald: As you get older there are are insurance and medical complications. I’m considering a licence where I can self declare but I don’t know. My ideal aeroplane would be a Pipistrelle “Virus”, a terrible name but such a great design, they do an all electric one too. I hope to get a trip in that machine of yours, what is it?

Jim: That would be great, you are welcome anytime. It is a Groppo Trail, like a modern take on a Piper Cub, not as powerful but I did my revalidation in a Cub and the Trail has more room for the pilot. Are you still working on projects?

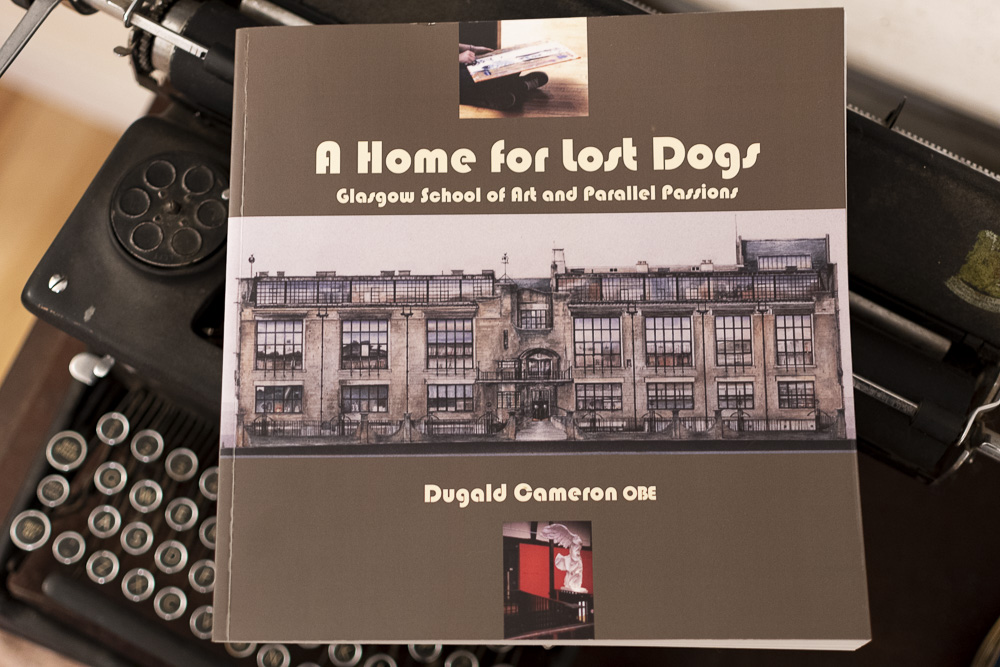

Dugald: Oh yes, I’m still an honorary professor, although I keep trying to retire. I love it though. I called my memoir “A Home for Lost Dogs” that’s what the Glasgow School of Art is, a place that can accommodate those that nowhere else can. A place where you can learn and think for yourself. I found my square hole there for my square peg. It really means an awful lot to me.

I started off as an apprentice at Rolls-Royce but it didn’t really suit me. Harry Barnes who was a the director of the Art School at the time and a great influence in my life, got me into the Industrial design course. He later received a Knighthood that was very well deserved. It also helped that art School started at 9:30 am while it was 7:30 at Rolls-Royce.

After I graduated I was offered a scholarship to Scandinavia that the Trades House of Glasgow paid for. I was involved in the development of hard adonising of aluminium. I’d also worked on the first medical ultrasound designs and both those projects later had aviation applications.

I was invited back to the Glasgow School of Art as an assistant and teacher so I did that in parallel with other design work.

In 1970 I saw an advert for the second chair of of design at the University of Delft in the Netherlands and wondered if I could get an interview. I got further than I expected and was actually appointed to the position by the Queen of the Netherlands herself, I was only 29 at that point.

Turning Down the Queen of the Netherlands.

At the same time a similar job came up back at the Glasgow School of Art and Harry Barnes offered it to me. I turned down the Dutch Queen and came back to Glasgow. Nine years later I became head of Design and Craft. A further nine years after that I became head of the school.

I am very proud of the fact that I was able to introduce an engineering degree to the School of Art, through a collaboration with the University of Glasgow. I wanted to rethink engineering education and I could see a flow through to mechanical engineering design as we already offered product design courses. We attracted the highest academic qualifications and I am also proud to say that we had a 50/50 gender split on the engineering course and that was in 1987. When I did my junior non diploma class in 1957 it was me and sixteen girls. There were no girls on the industrial design course when I was studying though.

Jim; So you kept your own art practice going while you were in charge at the Art School? That must have been a challenge.

Dugald: Oh yes! I always encouraged my staff to keep working on their own art as we were teaching students that they should be entrepreneurial. I had a real life example of doing that with the Squadron Prints business, it was not just a dry theory. I think it is important to lead by example. I introduced exhibitions of work created by staff every year. I am often asked how I coped with doing battle with authorities for funding, compliance visits and other challenging tasks. I tell them that I come home, have dinner with Nancy and retire to the studio to draw aeroplanes.

Jim: That’s a fine philosophy that seems to have served you very well. Thank you so much for your time and all that you have done for the aviation and art worlds.

I felt very privileged to then have a tour of Dugald’s private collection of art including some very large steam trains in oil and the original Phantom piece that started the business. It really is incredible work. Our conversation diversified but there is one final piece of advice that I shall embrace.

Dugald; “Do what’s important and forget the bullshit!”